Introduction: Current State of US Open Banking

In the United States, the growth of open banking has primarily been driven by market-led efforts. Voluntary agreements, screen-scraping practices, and some API-driven initiatives facilitated by data aggregators have supported a strong consumer appetite for data sharing. As of 2023, over 87% of U.S. consumers connect their bank accounts to technology apps1. In this environment, certain fintech companies have thrived through innovation. Challenger banks like Chime and neobanks such as Current have grown rapidly by leveraging open banking partnerships to offer seamless, app-based banking experiences. Even major players like PayPal and Square have capitalized on this ecosystem, integrating account and transaction data to strengthen their platforms.

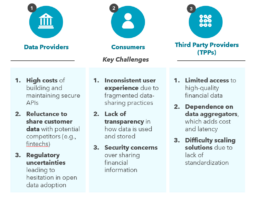

While some companies succeed, others face significant roadblocks due to inconsistent API standards, restrictive bank policies, and the technical challenges of integrating with multiple data sources. This fragmentation has created inefficiencies that limit the scale of open banking in the United States. The associated challenges affect multiple stakeholders. Consumers often face poor user experiences, including broken connections or delayed data updates, due to inconsistent API performance. Third-party providers struggle with fragmented access as banks implement varying standards or impose limits on the amount and type of data that can be shared. Meanwhile, banks grapple with the high costs of building and maintaining secure, reliable APIs, which makes them hesitant to invest in open banking infrastructure. These issues highlight the need for regulatory oversight to establish a broad open banking framework. Such a framework would ensure consistency across financial services providers of all sizes and varying levels of technological maturity.

Exhibit 1. Stakeholders

CFPB's Final 1033 Rule

On October 22, 2024, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) issued its final rule for implementing Section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act 2 3, aimed at addressing some of the aforementioned challenges in open banking in the U.S. Under this rule, financial institutions like banks and credit unions are required to provide consumers with access to their personal financial data at no charge, allowing them to share it with other providers.

Further, the final rule is a change from the initial proposition in 2023, which required financial institutions to implement APIs for data sharing but left the specifics of consumer consent unclear. The updated rule provides clear guidelines ensuring that consumer consent is both explicit and easily revocable, addressing previous concerns around privacy and security. This marks a significant step toward creating a competitive and consumer-centric financial ecosystem, enabling individuals to seamlessly access and share their financial data across platforms.

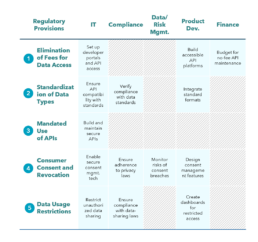

The regulation is designed to increase competition in financial services by ensuring that financial institutions (FIs) of all sizes have equal access to consumer data without incurring costs. However, those entities that are considered data providers such as banks, credit unions, and sizeable fintechs, will have to make substantial operational adjustments and compliance investments to adhere to the final rule. The final rule has 5 key provisions, covering the types of data shared, consumer consent management, methods of sharing data with authorized third parties, guidelines on the usage of said data, and mandatory no fee access.

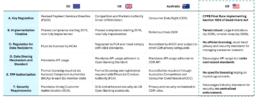

Exhibit 2. Final Open Banking Rule – Key Provisions

Direct and Indirect Impacts of the Rule

The CFPB’s Final Rule directly impacts how financial service providers can access and monetize consumer data, while also influencing future practices around security, consent, and data sharing.

- Elimination of junk fees enhances competition but may stifle innovation4: The CFPB’s prohibition on fees for data sharing allows TPPs and consumers to access data at no cost. This promotes competition by lowering entry barriers, enabling TPPs to offer consumer-facing services without the burden of paying data providers as part of their supply chain. However, this approach reduces financial incentives for data providers, who now lack revenue from data access fees.

In jurisdictions like the EU, banks can charge for premium API services, which encourages them to go beyond the regulatory minimum5. The CFPB, by contrast, mandates free access to all “covered” consumer data. This restriction may negatively impact the pace of API development, as providers may only comply with the minimum regulatory requirements rather than innovate beyond them.

- Standardization of data types benefits TPPs but adds compliance costs for data providers: The standardization of data types, such as transaction information and balance information, ensures uniformity across providers, facilitating easier integration for TPPs. For data providers, aligning structures can streamline operations by ensuring interoperability within TPP systems, but might also add to compliance costs. In fact, the Bank Policy Institute and the Kentucky Bankers Association filed a lawsuit challenging the rule, citing that the CFPB exceeded its statutory authority by making data providers carry the compliance burden6.

- Mandated use of APIs promotes security but raises operational costs for data providers: So far, the U.S. has lacked regulatory guidance on collecting and sharing consumer data, with open banking largely dependent on screen-scraping7. Screen-scraping involves consumers sharing their banking credentials with a third party, which then logs in on their behalf using automated bots. This practice often leads to the overcollection of consumer financial data, lacks proper consent verification, can be vulnerable to fraud, and may not securely store data. Mandated APIs enhance security in data transmission by ensuring data is collected and used only for purposes explicitly authorized by the consumer. This benefits all players by fostering consumer trust. However, all APIs must align with an information security program that meets the standards of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) or the FTC Safeguards Rule (page 38). This is likely to increase data providers’ cost of developing, implementing and maintaining APIs, with the cost of building a relatively simple API averaging around $20,0008, and large banks allocating approximately 14% of their IT budgets to API programs9.

- Consumer consent and revocation will encourage transparency, but without oversight, can be manipulated by data providers: To encourage transparency, authorized third parties and data aggregators are required to establish disclosures that confirm to consumers, prior to accessing data, their agreement to abide by the rules on data access and usage. However, the CFPB’s decision to let data providers determine the “authorization” of TPPs poses a challenge to this provision’s implementation. Although intended to allow providers flexibility to manage risks, this discretion may enable data providers to restrict competition by denying TPP access under broad risk-based justifications.

- Data usage restrictions will prevent data misuse, but affects data providers’ monetization opportunities: By restricting TPPs and data providers to only use data for “reasonably necessary” purposes related to the requested product or service, the rule limits the scope of how collected data can be leveraged. For consumers, these restrictions offer enhanced privacy, as data cannot be repurposed without explicit consent, reducing the risk of unsolicited targeting or advertising. However, this prohibition on cross-selling and other indirect data-driven marketing limits potential revenue streams for data providers and may affect the traditional data monetization models. For TPPs, limited data use could hinder expansion into diversified product offerings that rely on cross-utilizing data insights. This might compel TPPs to design narrowly focused products and services, which could stifle innovation in value-added features.

Exhibit 3. Impact of Final Rule’s Key Provisions on Open Banking Stakeholders

Comparative View Of Open Banking Models Across Geographies

Unlike the centralized, regulation-driven models of the EU, UK, and Australia, the U.S. approach to open banking under the CFPB’s Section 1033 rule is market-driven and decentralized. While the final rule mandates consumer data access and sharing, it relies heavily on industry initiatives (e.g., FDX standards) and voluntary adoption rather than prescribing uniform technical standards or licensing TPPs. This contrasts with the EU’s PSD2 and the UK’s Open Banking framework, which enforce strict API mandates and formal authorization for TPPs. The U.S. model fosters flexibility and innovation but lacks the interoperability of its international counterparts.

Exhibit 4. Comparative view of CFPB Final Rule vs PSD2/UK Open Banking regulations 10 11 12

Next Steps For Data Providers: Operating Models For Implementation

Data providers must adopt effective operating models to ensure seamless compliance and implementation of open banking provisions. Two models can be considered:

- CENTRALIZED OPERATING MODEL

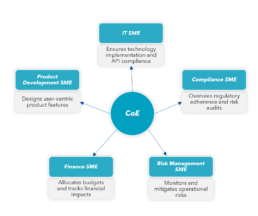

In the centralized operating model, the implementation and management of open banking provisions are overseen by a dedicated Center of Excellence (CoE). The CoE acts as the single point of accountability, consolidating responsibilities across functions and ensuring uniform implementation of standards. The CoE is staffed with subject matter experts (SMEs) from key departments, including IT, Compliance, Risk Management, Finance, and Product Development.

This model streamlines governance, reduces duplication of effort, and accelerates implementation by centralizing decision-making and execution processes. The CoE also assumes a project management office (PMO) role, coordinating cross-functional activities, monitoring progress, and addressing roadblocks.

Responsibilities of CoE:

- Define and enforce organization-wide standards

- Coordinate implementation efforts across functions

- Monitor compliance and track project progress

- Act as a single point of accountability for regulatory bodies

Exhibit 5. Centralized Operating Model

- FEDERATED OPERATING MODEL

In the federated operating model, individual functions within the organization retain responsibility for implementing specific aspects of open banking provisions. Key functions include IT, Compliance, Risk Management, Finance, Product Development, Legal, and UX Design. Each function independently manages its mandate while aligning with the organization’s overall governance framework. A cross-functional Steering Committee (SteerCo) acts as the coordinating body, ensuring collaboration across functions and addressing potential overlaps. SteerCo enforces standards and alignment with strategic objectives while allowing each function to maintain ownership over its responsibilities. This model promotes flexibility, enabling teams to adapt to department-specific challenges. The responsibilities of each functions is:

IT: Oversee API development, system integration, & tech updates

Compliance: Ensure adherence to regulatory requirements and data protection laws

Risk Management: Conduct risk assessments and implement risk mitigation strategies

Finance: Manage budget allocation & financial forecasting for compliance

UX Design/Product Development: Enhance user experience, product features, and service delivery.

Exhibit 6. Federated Operating Model

In Closing...

In markets with earlier regulatory pushes for open banking, such as the UK, API growth has fueled significant innovation among TPPs. The CFPB’s final rule has the potential to create similar opportunities in the U.S., enabling TPPs to offer personalized financial products while allowing data providers to monetize partnerships and value-added services. This regulatory shift could drive substantial revenue growth in payments, lending, and financial advisory services, fostering a more competitive and consumer-centric financial landscape.

However, as the regulation takes hold, many banks have expressed concerns. The legal complaint filed by a national bank and two banking associations argued that the CFPB exceeded its authority under Section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act by requiring banks to share consumer financial data with third parties not defined as “consumers”13. The plaintiffs also highlighted concerns over data security, economic strain from the prohibition on fees, and the delegation of compliance standards to private standard-setting bodies.

Given these challenges, banks face the greatest burdens in adapting to this new environment. They will need to invest heavily in secure API infrastructure, develop robust consent management systems, and navigate new compliance standards—all while managing the economic impact of fee restrictions.

To remain competitive, banks must evolve beyond traditional roles, potentially by embracing partnerships with fintechs, enhancing digital offerings, and rethinking customer engagement strategies. These adjustments will be essential for banks to turn regulatory challenges into growth opportunities in a more open and innovative financial ecosystem.