The Unbundling of Retail Banking

The Retail Banking Stack

THREE LAYERS

Not unlike a piece of software, retail banking can be portrayed as a stack comprised of 3 layers, where the complexity of each services can be abstracted into discrete segments and end products.

The top layer is the front end, or customer-facing side of the business. This top layer of the banking system can then be broken into three fundamentally different core competencies — deposits and customer accounts, payments, and credit.

The middle layer is the bank’s balance sheet and the infrastructure to implement and deploy products like checking accounts, payments and credit.

The bottom layer is the underlying infrastructure of services and software that forms the “plumbing” of the banking system, connecting the various balance sheets together. Examples are the Core Banking System (CBS) and settlement processes necessary for a financial system to function.

Today, most incumbent banking players are vertically integrated, occasionally outsourcing certain back end functions such as clearing, settling and reconciling accounts. However, this model is bound to break apart, as the stack unbundles into horizontally integrated companies focused around each component of the value chain.

"The vertical model is bound to break apart, as the stack unbundles into horizontally integrated companies focused around each component of the value chain."

MODULARIZATION: VERTICAL TO HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION

Historically, when customer data was primarily recorded on paper and employee communication was limited, the most efficient organization model of banking was vertically integrated companies with different divisions: IT, Customer Service, Sales, etc. In this model, the transaction costs of coordinating the different components of retail banking under a single roof were too high and customer attention was limited to their local branch. Consumers were unwilling to undergo the hassle of literally traveling between various providers for services. As part of this operating model, companies become optimized to deliver the best performance of each individual division rather than the overall end product.

This organizational structure carries many flaws. For example, the IT department of a bank has to wrangle with a culture that emphasizes other departments as “rainmakers” and themselves as back office cost centers. IT is relegated to a support role, lacking the internal sway and prestige to attract the best talent. Can anyone remember a bank’s CEO coming from the IT department?

However, modern technology is addressing this fundamental issue of complex coordination by implementing a set of communication protocols. Customer data can be easily accessed across a set of standardized APIs and permissions. Account and transaction information is easily exposed securely to a third party in real time by a network call.

This disentangles the customer interface from the core services, allowing each to specialize in different parts of the value chain.

As a result, consumers can now use that modularized service as an independent product that tracks expenses and withdrawals to monitor behavior and encourage more prudent habits. That same software can also be used to communicate with the user’s payments service and alert the customer at checkout of, say, “profligate behavior” on a festive Friday evening. That account can simultaneously be linked to draw information from a wealth management product to build a more complete profile of the consumer’s financial health. That same product can maximize returns by making automatic and precise withdrawals from riskier, higher yield accounts filled with equities and fixed income when cash is needed. Similar to the App Store on the iPhone, there would be a plethora of companies developing new services. Consumers would have access to a diverse product offering unmatched by a vertically integrated offering running on software designed in the 70s. All of these tasks are enabled by software’s dramatic reductions in coordination costs and improved communication.

The move to horizontal integration turns banks into modules focused on delivering the best service possible. For example, front end companies only concern themselves with the customer-facing portion of the retail banking business, optimizing solely on developing superior customer services. As a result, each middle manager’s P&L is directly tied to the end product rather than one component of it, aligning the incentives of product development with profitability.

The ultimate result of unbundling are the enormous opportunities for a multitude of competitors to insert themselves where previously one bank stood, driving down margins and expanding choice. The vertically integration model finds itself collapsing into individual modules integrated horizontally.

"The ultimate result of unbundling are the enormous opportunities for a multitude of competitors to insert themselves where previously one bank stood, driving down margins and expanding choice."

THE ‘AMAZON WEB SERVICES’ OF BANKING

On the lower end of the stack, the conversion of internal processes to software requires a platform to house modularized front end. Banks like Citi, Capital One and BBVA are already building developer platforms that leverage the core functionality of their massive infrastructure and services for other companies to innovate on top of.

This is a very similar story to what Amazon did for cloud computing. Amazon developed, maintained and ran the software on its on servers, giving developers access to the most mature server platform. Companies no longer had to put up with the high fixed costs of building their own cloud infrastructure which would be likely inferior to Amazon Web Services anyway. Meanwhile, Amazon can amortize the expense over a much larger user base, driving down average costs, and allow businesses to pay as they grow.

These “Banking as a Service” (BaaS) platforms have the potential to become the AWS equivalent for financial services: a one-stop-shop to build financial services products on top of.

Building a platform requires banks to cede the top layer of the stack to third parties. Most have been unwilling to do so citing competitive, security and regulatory risk. In fact, these BaaS products allowed Simple, a bank, to be built by “2 guys in an apartment” in less than a year – case in point. Despite the incumbent banks’ natural resistance, competition, superior user experiences, and new third party products may force them to give in anyway.

However, building the AWS of banking is no small feat. Much of the banking system relies on core banking system software that is over 20 years old, runs on mainframes and is unable to process transactions in real time. This makes extending system software to generate a modern, robust banking platform API exceedingly difficult. Yet, it is not impossible. BBVA Compass took the operationally risky and expensive route of replacing its aging core banking systems from its various acquisitions with a real time, modern system. This harrowing experience cost $360 million, 3 years of engineering development and was the first Core Banking System (CBS) transplant in the United States in over 15 years. The Alnova CBS is efficient enough to provide low-cost solutions that are extendable like a modern software platform in any other industry.

Banks who are able to navigate this expensive and difficult transition will be able to develop a modern, cost-effective platform, becoming part of the very fintech industry that threatens to make them obsolete.

The drawbacks to this strategy of open banking is that fostering an ecosystem is difficult, especially for a company cannibalizing a large portion of their existing business. An entire company culture and system of processes need to be developed to create an organization that is competent at building ecosystems that others can thrive in. Banks would have to be content with letting, or dare encouraging, others to extract value from financial services. While a potentially lucrative opportunity, this requires a change in mindset on how to approach markets, develop products, and think about margins.

"Banks who are able to navigate this expensive and difficult transition will be able to develop a modern, cost-effective platform, becoming part of the very fintech industry that threatens to make them obsolete."

The Current Landscape

CORE COMPETENCY OF INCUMBENT BANKS

Amidst this unbundling and reshuffling of the modules, what advantages do incumbent banks have? While offering an aggregated bundle of services is becoming less and less crucial, they still maintain a crucial comparative advantage: regulatory management and compliance. The financial services industry is one of the most heavily regulated industries in the global economy. Large banks have become increasingly adept at navigating this byzantine system of complex regulations with onerous requirements that smaller, upstart competitors have difficulty coping with. Even when developing new fintech services, there are a dizzying array of disclosure requirements such as Sarbanes Oxley and Know Your Customer laws that vary by regulatory jurisdiction.

One of the arguments in favor of fintech startups providing unique services is that existing regulations do not (yet) inhibit them. Conversely, investors attach substantial risk premiums to these companies due to the vast degree of regulatory uncertainty. Often a startup’s survival is predicated on the whims of regulatory discretion. Recently P2P lending startups suffered a major setback when the FDIC issued a dictum that restricted their ability to sell securitized products to banks, causing a plunge in their valuations and future prospects. Simultaneously, investment banks like Goldman Sachs intensified their interest in entering the industry since the ruling did not inhibit them.

Established firms (who possibly hold sway over policy makers), are much better positioned to weather, or even co-opt, regulatory turmoil.

The task of managing balance sheet risk for large pools of capital is extremely complex, highly sought after, and plagued by high fixed costs. Startups do not have the quantitative expertise to effectively maneuver through these regulations, but incumbent banks are used to doing this daily.

Despite changing industry fundamentals, incumbent banks appear well positioned to maintain their role as managers of large balance sheets, ensuring them a comfortable spot in the middle layer of the stack. They have all the pre-existing infrastructure to manage deposits, execute settlements, securitize assets, generate net interest margin and comply with regulations already built. Large, incumbent banks will not disappear. But their ability to adopt a new business model that exploits their core competency while managing the decline of other divisions will be tested.

FINTECH REGULATORY HURDLES

New banking startups can be split into two categories.

The first one encompasses neo-banks, like Simple and Moven, who strive to provide an alternate customer experience while leveraging existing banks to handle their deposits transactions.

The second one refers to “full-stack” banking startups that aim to acquire a banking license while exclusively maintaining a digital presence and services.

The latter category has faced significant regulatory challenges. In the UK, Atom Bank and Tandem were issued licenses in 2010, after an extensive and costly regulatory process, – the first licenses issued to a new bank in the UK in over 100 years! Comparatively, the FDIC has refused to approve “full-stack” digital banks. Without FDIC insurance, a new bank will be unable offer a deposit account acceptable to consumers. Meanwhile, Washington regulators have decided to put new fintech approvals on hold and focus energies on specific segments of the industry, stunting growth.

Capital requirements further restrict “full-stack” fintech banks, by forcing them to grow profitably, or in plain English, slowly. This conflicts with the expected growth trajectory of a startup: forego monetization early on to mature the product and scale. Consequently, holding deposits heavily constrains a startup’s ability to innovate, impinging growth.

These impediments add further credence to the thesis that incumbent banks will remain the managers of deposits and large balance sheets, allowing fintech companies to flourish further up the stack. Startups who decide to take deposits will grow far more slowly and be fewer in numbers. The recent acquisition of Fidor by BCPE aims to alleviate capital constraints by providing Fidor with a large, mature balance sheet while maintaining its operational independence.

FIDOR AND THE FINTECH BANKING PLATFORM

German banking startup Fidor perhaps represents the best example of the macro trend of unbundling and creating a broader platform for other players to build on. Fidor is seeking to build a banking platform company from first principles, modeling it off the iPhone. From the start, the founders’ core belief was that “if it is not coded, it does not have value.” Fidor had to be a digitally native product with an organization capable of fully extracting the benefits. The case for Fidor is that banks who have more money, engineers and experience are unable to build next generation financial services because they are weighed down by legacy baggage. Their incentives, culture and organization are predicated on serving existing products to existing consumers, through existing channels.

A clean start gives Fidor the advantage in building the currently nonexistent.

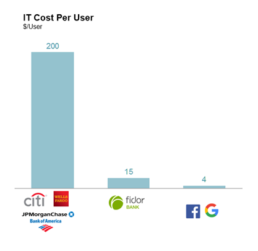

Fodor's IT expenditures per account are less than 10% of a conventional branch bank, making their cost structure more similar to a Google or Facebook than a Citigroup or JP Morgan Chase.

A software native banking infrastructure devoid of legacy costs allows Fidor to conduct business at a fraction of the expense of conventional banks while implementing the most modern and advanced protocols like Ripple. Their IT expenditures per account are less than 10% of a conventional branch bank, making their cost structure more similar to a Google or Facebook than a Citigroup or JP Morgan Chase. Additionally, their net interest margin, a critical factor that accounts for 50% of commercial banking profits, was 6% in 2015, more than 2x the industry average in the United States. Superior net interest margin performance will only increase in importance as the other half of revenue generated by fees heads to zero. Even more surprisingly, their net interest margin has been growing rapidly in an environment with increasingly lower real and nominal interest rates and falling industry averages.

The goal of FidorOS was to build a platform that made “innovation happen in a compliant way” by acting as a bridge between core banking and customer interfaces, removing complexity. One of the key achievements of Fidor’s software is that it is built to be interchangeable with various core banking systems found across countries. This abstracts away the core banking stack, making FidorOS the target development platform that banking products are built on top of instead of the CBS. In effect, their aim is to create “a global industry standard for modern, online banking” that is lucratively dependent on them to function and impossible to transition off of.

FidorOS allows clients to focus on the last mile of delivering the consumer-facing services, allowing non-traditional players to provide financial services. Telecom providers like O2 and Telefonica are taking advantage of this opportunity by leveraging their strong distribution channels and go-to-market ability through their mature retail and mobile presence as network operators. O2 and Telefonica are just 2 examples of the bevy of potential non-traditional entrants willing to introduce new, disruptive business models and products that are enabled by Fidor.

The Path Forward

The vertically integrated banking stack is effective at offering branch-based retail services. It makes it difficult for a new entrant to compete against highly efficient incumbents who have spent decades gathering expertise and economies of scale. Yet, these conventional banks are predicated on a world without mobile, sophisticated telecom and cloud computing. These factors shift the axis of optimization, leading to an unbundling of the banking stack.

In the search for new customers, forward-looking banks like BBVA and Citi have started thinking of themselves as platforms.

In retrospect, this may be seen as a retreat to core competencies that are still relevant in an evolving market, letting other firms handle consumer interactions. The fundamental question banks face is determining who and what form will they serve customers in a world where traditional services are becoming unbundled.

Amazon Web Services and the smartphone are most responsible for the last decade’s boom in startup activity in Silicon Valley, ushering in an IT renaissance. AWS gave any programmer with a laptop the ability to inexpensively scale to millions of people without paying millions of dollars or committing months of engineering. This dramatically lowered the barrier to entry and experimentation, creating an environment of ‘permissionless innovation.’ A few dozens of engineers can now create sophisticated services that scale to hundreds of millions of users. Banking as a Platform will have the same impact on financial services as AWS, providing cutting-edge banking infrastructure while foregoing the need for regulatory approval and a host of licenses. This will be the impetus for an explosion of new fintech startups fielding new ideas, products, and services.