Cities are the lifeblood of vibrant economies the world over – 70% of the world’s population is expected to live in cities by 2050.1 However, the COVID-19 outbreak has brought bustling urban landscapes to a standstill. Few have moved about their daily lives because of social distancing and lockdowns, so demand has dropped precipitously. Urban mobility has in a short period seen both the cramped high and the desolate low.

Urban mobility includes distinct journeys people make in a city as well as infrastructure, traffic management, road safety, developmental investments, and any satisfaction of urban needs.2 The COVID-19 outbreak has, for the time being, removed the essential figure– the people –from this definition. With mobility on pause, this is a moment of reflection and opportunity.

The way people commute has a huge impact on not just the mobility space, but also on the ancillary ecosystem. Being a crucial part of daily life, commutes dictate choices, preferences and day-to-day decisions. For example, if one decides to drive to work, they might stop for coffee at a drive-thru; if one takes the subway to work, they might grab a coffee at the subway station; and, if one pays for subway tickets using a card, they are likely use that card to also pay for the coffee. Mobility is seen as an elemental part of the ecosystem people thrive in and has the ability to dictate human behavior, preferences, and opportunities. In the past, payments firms have used mobility as a pathway to shape consumer behavior. Even during this pandemic, that pattern continues to hold true. In this paper, we aim to call out the foreseeable changes in urban mobility and the impact of the changing ecosystem on the world of payments.

COVID-19 IS TURNING PEOPLE OFF MASS TRANSIT

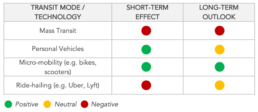

Exhibit 1: Impact of the pandemic on tranit modes

The pandemic is profoundly disrupting mobility, as the short-term impact on mass transit has been decisively negative. In April 2020, ridership across New York City’s MTA, the nation’s largest public transit system, fell by 60% on subways and as much as 90% on commuter trains…in San Francisco, rail ridership on BART was down a staggering 90%…booking on Amtrak has plunged 50%. In mid-March, “freeways and surface streets in Los Angeles were moving 35% faster than normal.”3 The pandemic’s shock has hurt incumbent systems.

In the mid- and long-term, as the economy begins to recover and the world starts reopening, it will be a challenge for transit agencies to achieve their already stagnating ridership numbers pre-pandemic. Historically, mass transit ridership and employment have been intertwined. With unemployment skyrocketing, expect transit ridership to rebound slowly.4 The staggering jobless claims in the United States and elsewhere are not expected to recover for a while. Consequently, commuters will take a long time to return. Transit agencies need to think and act creatively considering strategies that can inspire and expand their mandate beyond incumbent systems, most likely through micro-mobility and innovative technology.4

ALTERNATIVE TRANSIT MODES ARE PROVING MORE APPEALING

Micro-mobility is already filling initial gaps left by mass transit. In the new normal, this lightweight mobility suited for short trips is increasingly more relevant. In early March, bikeshare ridership saw an initial surge in cities like New York and Philadelphia.5 This phenomenon started in the initial stages of the pandemic as people began to worry about the cramped quarters of mass transit. And, as concerns linger past the pandemic, the phenomenon will likely shape the future of movement in cities. For example, in China, where cities have started recovering and some restrictions have been lifted, bikeshare in Beijing saw rides increase 187 percent. There will be a gap to fill as citizens transition back to movement, and micro-mobility is nimble where mass transit cannot be. The important next step for players in this space will be making their place permanent in the new normal.

While micro-mobility has an element of ‘sharing’ that might concern those worried about transmission of illness, many providers also have direct-to-consumer options. Indeed, those players that offer “direct-to-consumer e-scooter sales, such as Bird, are likely to gain an advantage.” Even though business models differ, the experience and technology being built out in micro-mobility will play an important role in shaping the future of urban mobility.6

Personal vehicles may see a rise in use if not a rise in purchase. A recent study found that “two out of three respondents say that they prefer their own car to public transport—twice as many as before the pandemic.”7 A knee-jerk reaction to not trusting mass transit is, at least for the short term, a push toward cars. However, for those looking to purchase cars, the economic crisis that has resulted from the pandemic has delayed plans. A survey of car buyers in April, indicated that 79% have postponed their purchase due to the pandemic. The upcoming recession will likely delay such plans further.7

Ride-sharing has a mixed outlook for the immediate future. The prediction for ride-sharing players like Uber and Lyft is a complicated one to make. 39% of people surveyed expect to reduce or stop using ride-sharing, but 43% said they would continue to use them the same amount.8 Ride-sharing has suffered due to people not wanting to use shared vehicles with the risk of contagion; however, innovative business segments of ride-sharing leaders, like Uber Eats, are picking up slack as people rely on food delivery while sheltering in place. The challenge for these firms will be prioritizing measures for health to convince customers they are safe and remain relevant. Picking up on this cue in early May, Uber instituted mandatory mask wearing policies and a ban on front seat passengers.

As peoples’ preferred modes of transport change in the short- and long-term, the way they pay for journeys (and other ancillary purchases) will also change. Transport stakeholders, payment providers, and local governments need to be prepared to take or even lead this transformative journey.

ACROSS ALL MOBILITY TRANSIT MODES ARE PROVING MORE APPEALING

Whether traveling by micro-mobility, ride-sharing, personal vehicle, or eventually mass transit, people will want to minimize the contact they have with surfaces and others during points of contact, like payment.

In the mass transit space especially, contact between transit personnel and riders, as well as amongst riders, needs to be minimized.

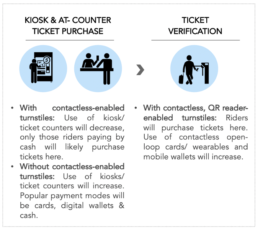

Exhibit 2: Alternative payment modes in a metro journey

The two obvious points of contact are:

- Ticket purchase – At kiosks, at counters with transit personnel

- Ticket verification/ checking – At turnstiles with readers, manual checking

As use of cash declines due to the perceived risk of communicable germs, there are several solutions that are likely to take center stage.

The pandemic has made way for contactless technologies to come to the forefront and be appreciated for the ease, convenience, and safety they allow users over cash and traditional card interactions. While they may be known as “tap-to-pay” or “tap-to-go,” in reality contact is not crucial – a user just has to wave the card/ watch/ smartphone close to the card reader.

The “no-contact” tenet is attractive in the new normal, especially since it converges on both original points of contact in a rider’s journey (see Exhibit 2).

Contactless cards will empower the shift toward no contact. In an effort to minimize physical exchanges of any form, riders are likely to start using contactless credit/ debit cards.

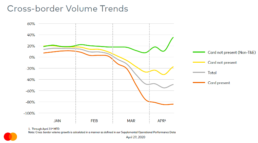

To that end, early numbers from Mastercard reported a 40% jump in cross-border contactless payments* during the first quarter of 2020 as the pandemic worsened (see Exhibit 3; Source: MasterCard earnings report Q1, 2020). Receptive to the increased demand of contactless payments, more than 50 markets increased tap-to-pay limits, including 26 European countries, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.9

Exhibit 3: Jump in Mastercard contactless payment volumes in Q1 202010

As consumers get accustomed to using contactless payments, a “halo” effect of an uptick in spending due to the ease and safety of the purchasing process is likely to be seen in mobility transactions and beyond.

How far along are issuers in the journey to issue contactless cards? In U.S., banks such as Chase, Wells Fargo, and TD Bank are past midway in rolling out contactless – issuing contactless cards for all new customers and aiming to replace traditional cards as they expire. As the mobility-driven demand increases, issuers will make a quick transition to contactless cards. In June 2019, BofA aggressively launched contactless cards in 3 cities, aimed at serving their transit systems that enabled NFC. TD Bank followed a similar pattern to issue contactless cards, by prioritizing users who had in the past used their credit or debit card to pay for a mass transit ride.11

While the burden of card issuance rests with the issuers, the burden of enabling contactless acceptance rests with transit operators and other mobility stakeholders.

Several cities like London, New York, and Rio de Janeiro have open-loop contactless card readers enabled in public transport modes, which are going to see an increased usage of contactless cards and migration from any other payment methods they currently accept. However, the majority of cities around the world either use closed-loop systems (tokens/magnetic strip cards) or accept cash.

With dwindling revenue, falling ridership, and increased cost of sanitization, are transit operators in a position to overhaul the infrastructure?

Varied stakeholders have opportunities to enter into public-private partnerships to support contactless acceptance. Payments providers will capture additional revenue in transit systems and eventually in other realms of commerce through contactless usage, so supporting efforts to implement contactless acceptance in mobility is crucial. The pandemic also presents an opportunity for countries to have a nationwide contactless payment card, which could be used to streamline payments to one card for public transport, groceries, fuel, parking and all other small purchases.

Players like Uber and Lyft already accept payment by cards stored on their apps and via mobile wallets, so they are unlikely to require much change. However, vast informal public taxi operators, like in Mexico City, may need to prepare to shift to contactless acceptance. To accept contactless payments in person, drivers will need a contactless POS system. This opens up a previously inhibited audience for m-POS providers to partner with.

A well-known barrier to contactless adoption is the world’s unbanked population with no easy access to contactless or digital payment forms. Tencent and SoftBank-backed fintech startup Ualá in Argentina is working with the Argentine government to knock down this barrier. It offers a combination of an app and a physical prepaid card, allowing users to make payments physically and online. In a largely cash-based economy like Argentina, Ualá’s mobile app and online payment system offer an attractive alternative, which is reflected in a 300% increase in transactions on their platform in April 2020.12

While contactless will be the driving force, several other technologies are likely to be part of the target-state. We will next look at burgeoning concepts that could become the norm in the long-term and may be fast-tracked due to the pandemic’s reprioritization of the mobility space.

CONTACTLESS IS JUST THE BEGINNING, AS PAYMENTS WILL SEE A TECHNOLOGY BOOM

The breadth of digital wallets accepted to pay for mobility is likely to increase. Apart from digital wallets like Apple Pay, Samsung Pay, which are contactless technologies that allow payments with a swift wave near the reader, several other mobile wallet/ digital wallet solutions like PayPal, Venmo, Paytm will experience upticks in use as they make the payment process one-click, contactless, and quick. Expect these to be integrated into open-loop transit systems across the world in the future. In addition to their adoption in mass transit, wallets like Venmo or Paytm could be frequently used by the informal mobility sector as riders pay for cabs, rickshaws, and bike rides using these platforms.

The concept of “car commerce” could take off with the rise of personal vehicle use. This initiative would allow payments firms to capture transactions through the journey of a car ride, such as drive-through purchases, fuel purchase, toll fees, and parking fees.

As a concept, “car commerce” is still a work in progress – there is a lack of interoperable systems, competing approaches from incumbents, and safety concerns about distracted driving, but the pandemic presents an opportunity for car commerce to boom once an ideal blueprint is realized.

In the safe haven of their car, owners/ riders of private vehicles feel safeguarded from the world outside. This frame of mind may likely influence purchases made by riders (mostly from inside the vehicle).

Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) remains a future-state goal. The broad ecosystem of mobility options in any given city could be united by one technology platform. Creating seamless customer journeys within cities through technology could be fast-tracked as old preferences are broken.

In its target state, a MaaS experience will allow a commuter to plan a multi-modal journey, make payments for the journey in a single app and have access to traffic, congestion, and optional route insights to help plan the journey. A future transition to MaaS will support the “no-contact” tenet of the pandemic seamlessly, making it a popular route to success for mobility players.

MaaS systems will allow urban environments to integrate their existing and recovering mass transit systems with innovative modes such as micro-mobility. For example, New York City has added more space for cyclists and other micro mobility users since the pandemic, while Bogota, Colombia has added 76Km of cycle lanes to their streets almost overnight. Mexico City and London have also seen benefits from increased cycle networks. None of these new micro-mobility networks are connected to mass transit yet, but a MaaS interface would allow them to be connected.13

IN CLOSING…

This pause in life has instigated a reevaluation of mobility. As social distancing and sheltering in place ease, cities could revert to their traditional, and inefficient, status quo. However, there is significant opportunity for payments firms to capitalize on the need for contactless mobility.

On the technology front, fintechs and MaaS-techs can push the boundary of mobility but will need capital and support. Payments firms as well as fintech- and mobility-focused private equity firms and venture capitalists have an opportunity to invest in leading startups that will shape the future.

And, both the private and public sector will be in the trenches to modernize mobility and adapt it to the post-COVID-19 world. Public-private partnerships should empower cities, providing them with both resources and innovation, to reshape the way citizens travel. Municipal governments must catalyze partnerships with both payments and mobility stakeholders to get their citizens back to work safely and their economies moving.

Now is a better time than ever to pivot to the new age of contactless mobility.